Let’s play a game of Contrast — between a multi-party system, the kind we could have with a few changes to our election laws (and no need for any amendments to the Constitution), and our existing two-party system. Let’s see how this difference would affect the current scramble to find a new Speaker of the House.

In order to win a majority of the 435-member House, a nominee for Speaker needs a majority of 218 votes. Currently, Republicans have 247 representatives versus Democrats’ 188. It seemed that Rep. Kevin McCarthy could have secured the 218 he needed from Republicans — but he withdrew from the contest on Thursday. Now, people are pressuring Rep. Paul Ryan to run — the only other member who (according to Beltway consensus) could get 218 Republican votes. But he says he doesn’t want the job.

Another possibility (according to many) is to choose a non-member as Speaker. The Constitution says only, “The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers” — it doesn’t say he or she must be a current member of the House. This would be an unprecedented move, as all of our Speakers have been members. But it would certainly be an interesting development — or at least experiment.

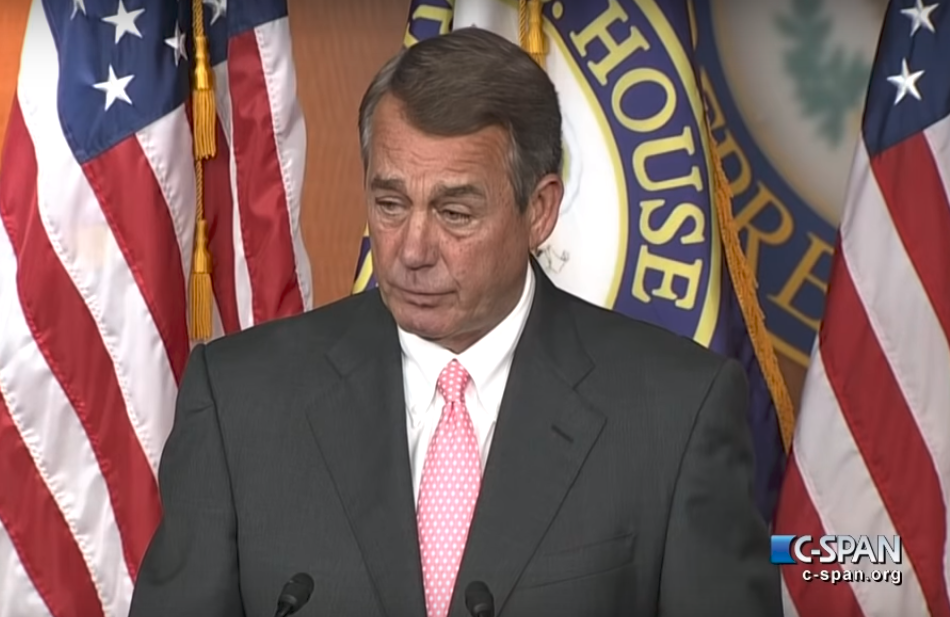

What if Paul Ryan can’t be convinced? What if no one outside the House wants the job? Does Congress shut down? Or does poor John Boehner have to trudge on in a job he visibly hates?

What’s important to realize is that this contest is based on the premise that the Republicans should be able to choose a Speaker with no input from the other side. Sitting in the majority, they have the power to do this, in theory — that is, if they can agree on someone. The problem is, today’s Republican Party is divided, and at least 30–40 of them are Tea Party Republicans who don’t want to accept anyone who won’t pursue their radical-right agenda.

But the whole House must vote on the Speaker. It’s only thanks to our two-party system, and the rules they’ve instituted for themselves, that we have a tradition of letting the majority party decide on a Speaker by themselves — then bring it to the floor to rubber-stamp a predetermined decision.

What if no party had a majority? This would very likely be the case, most if not all the time, if we had a multi-party system. Under such circumstances, the entire House would be involved in the decision. No candidate might be able to secure a majority of votes. But winning by majority is not prescribed as a requirement by the Constitution. It’s just a requirement of the current rules.

In fact, in the 34th Congress of 1855–57, there was no majority party, and no candidate who could win a majority of votes. (Democrats and Republicans shared power with the American Party, commonly known as the Know-Nothings.) Faced with a deadlock, the House agreed to change the rules to allow the Speaker to be elected by plurality, and Nathaniel P. Banks of Massachusetts was elected.

Imagine if they agreed to something similar today. Even better than plurality, they could use instant-runoff voting — or simply a series of votes, with the last-place candidate dropping out after each, until someone got a majority. This process would yield a Speaker that the whole House could live with, even if he was nobody’s first choice. Surely this is closer to the process the framers must have imagined than one in which a single party decides on its own.

Is there any chance this might actually happen? Probably not, as long as we have a two-party system. But it’s time for us to stop taking that for granted, and start thinking outside the box.